On Saturday, the capital of Libya, Tripoli, witnessed the country’s heaviest fighting in two years.

What led to the latest events?

2011

Libya's fault lines emerged as local factions took opposing positions in the NATO-backed uprising that toppled Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, the de facto leader of Libya since 1969.

An attempted democratic transition turned into chaos as armed gangs established local power bases and banded together around rival political groupings, seizing control of economic assets.

Pro-Gaddafi protests in Tripoli, May 2011

Pro-Gaddafi protests in Tripoli, May 2011

Libyan rebels after entering the town of Bani Walid

Libyan rebels after entering the town of Bani Walid

Caricature of Gaddafi, Al Bayda, April 2011

Caricature of Gaddafi, Al Bayda, April 2011

Hundred anti-Gaddafi protesters in Benghazi, 25 February 2011

Hundred anti-Gaddafi protesters in Benghazi, 25 February 2011

Protests on Al Oroba Street, Bayda, 13 January 2011

Protests on Al Oroba Street, Bayda, 13 January 2011

2014

Following the battle for Tripoli in 2014, one faction, including the majority of parliament members, moved east and recognized Khalifa Haftar, a Libyan-American politician and officer, as military commander, eventually establishing a parallel government.

Protesters stage a large demonstration in Shahat against the GNC's mandate extension plan

Protesters stage a large demonstration in Shahat against the GNC's mandate extension plan

2019

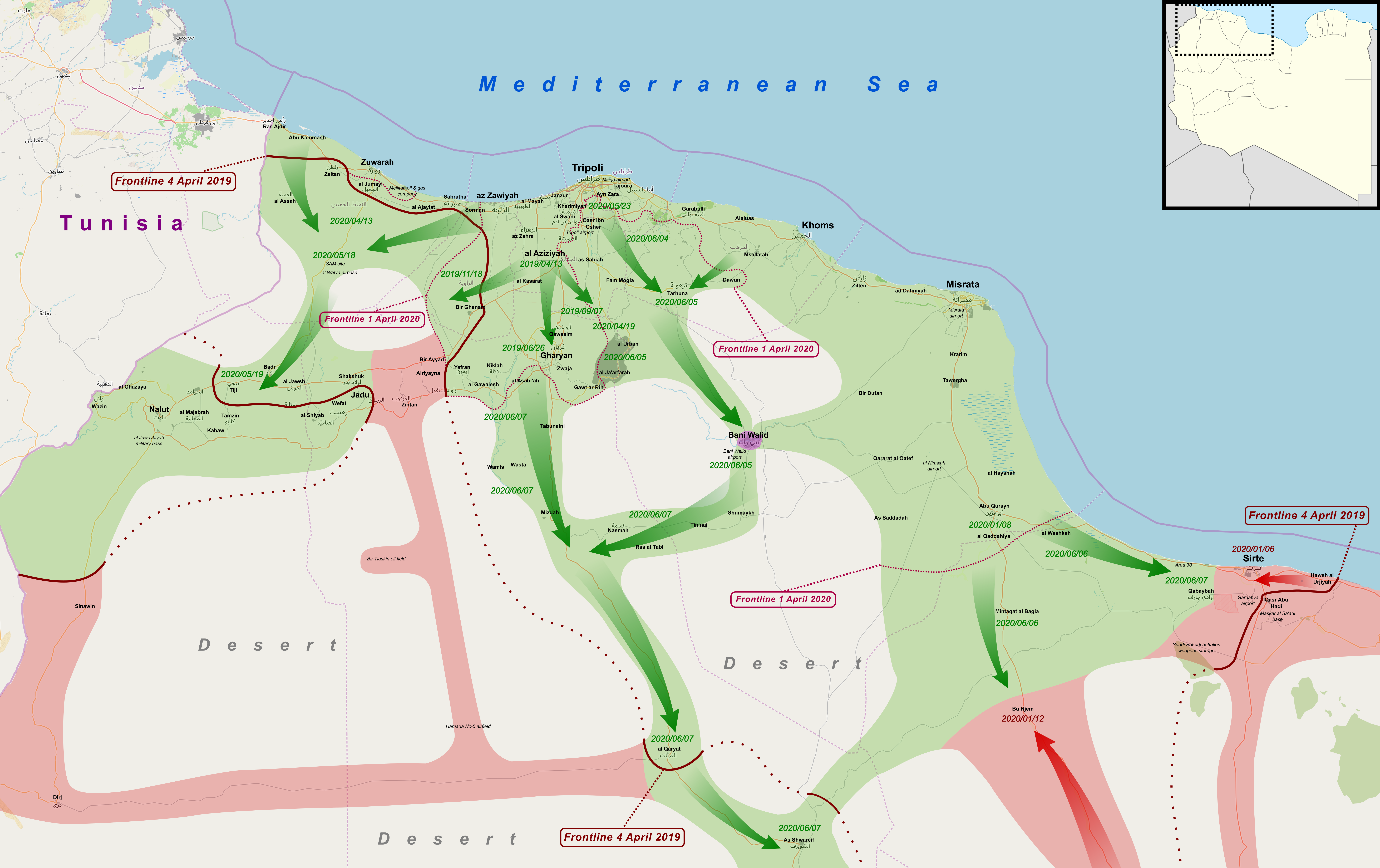

A UN-backed agreement resulted in the formation of a new internationally recognized government in Tripoli, but eastern forces rejected the agreement, and Haftar's Libyan National Army (LNA) assaulted the capital in 2019.

Map showing the Libyan National Army operation to retake Tripoli and the rest of Libya from the Government of National Accord and allies

Map showing the Libyan National Army operation to retake Tripoli and the rest of Libya from the Government of National Accord and allies

2020

The feuding armed factions that controlled western Libya joined together to support the Tripoli government against Haftar, repelling his invasion in 2020 with the assistance of Turkey, resulting in a ceasefire and a new UN-backed peace process.

2021

The peace process resulted in the formation of a new Government of National Unity led by Prime Minister Abdul Hamid al-Dbeibah, with the mandate to oversee national elections slated for December 2021, however there was no agreement on voting regulations, and the process collapsed.

Holes are seen in the windshield of a destroyed car following clashes in Tripoli, Libya August 28, 2022. REUTERS/Hazem Ahmed

Holes are seen in the windshield of a destroyed car following clashes in Tripoli, Libya August 28, 2022. REUTERS/Hazem Ahmed

A man stands next to a building burned during yesterday's clashes in Tripoli, Libya. August 28, 2022. REUTERS/Hazem Ahmed

A man stands next to a building burned during yesterday's clashes in Tripoli, Libya. August 28, 2022. REUTERS/Hazem Ahmed

Smoke rises in the sky following clashes in Tripoli, Libya, August 27, 2022. REUTERS/Hazem Ahmed

Smoke rises in the sky following clashes in Tripoli, Libya, August 27, 2022. REUTERS/Hazem Ahmed

People inspect the damage following clashes between backers of rival governments in Libya's capital Tripoli, on August 28, 2022.

Mahmud Tukria / AFP

People inspect the damage following clashes between backers of rival governments in Libya's capital Tripoli, on August 28, 2022.

Mahmud Tukria / AFP

Is a political deal possible?

The powerful eastern faction of Haftar, led by parliament speaker Aguila Saleh, has shown little inclination to compromise in its goal to depose Dbeibah and reinstate Bashagha.

However, with Bashagha seemingly unable to form a coalition of western factions capable of installing him in Tripoli, they may have to reconsider.

Turkey's ongoing military presence surrounding Tripoli, where it kept air bases with drones after assisting in repelling the eastern assault in 2020, suggests that another Haftar offensive against the city is unlikely for the time being.

Some politicians have proposed another attempt to build a new administration that can be accepted by all parties, which Dbeibah is likely to oppose.

Meanwhile, diplomacy has stalled, and consensus on how to hold elections appears to be further away than ever as a long-term solution to Libya's political conflicts.

International efforts to mediate a deal have been complicated by disagreements among the countries participating, as well as by local forces that many Libyans believe want to avoid elections in order to keep control.

Many Libyans fear that whatever the outcome of the next round of discussions and positions would be followed by another round of violence.

How does all of this affect Libya's oil?

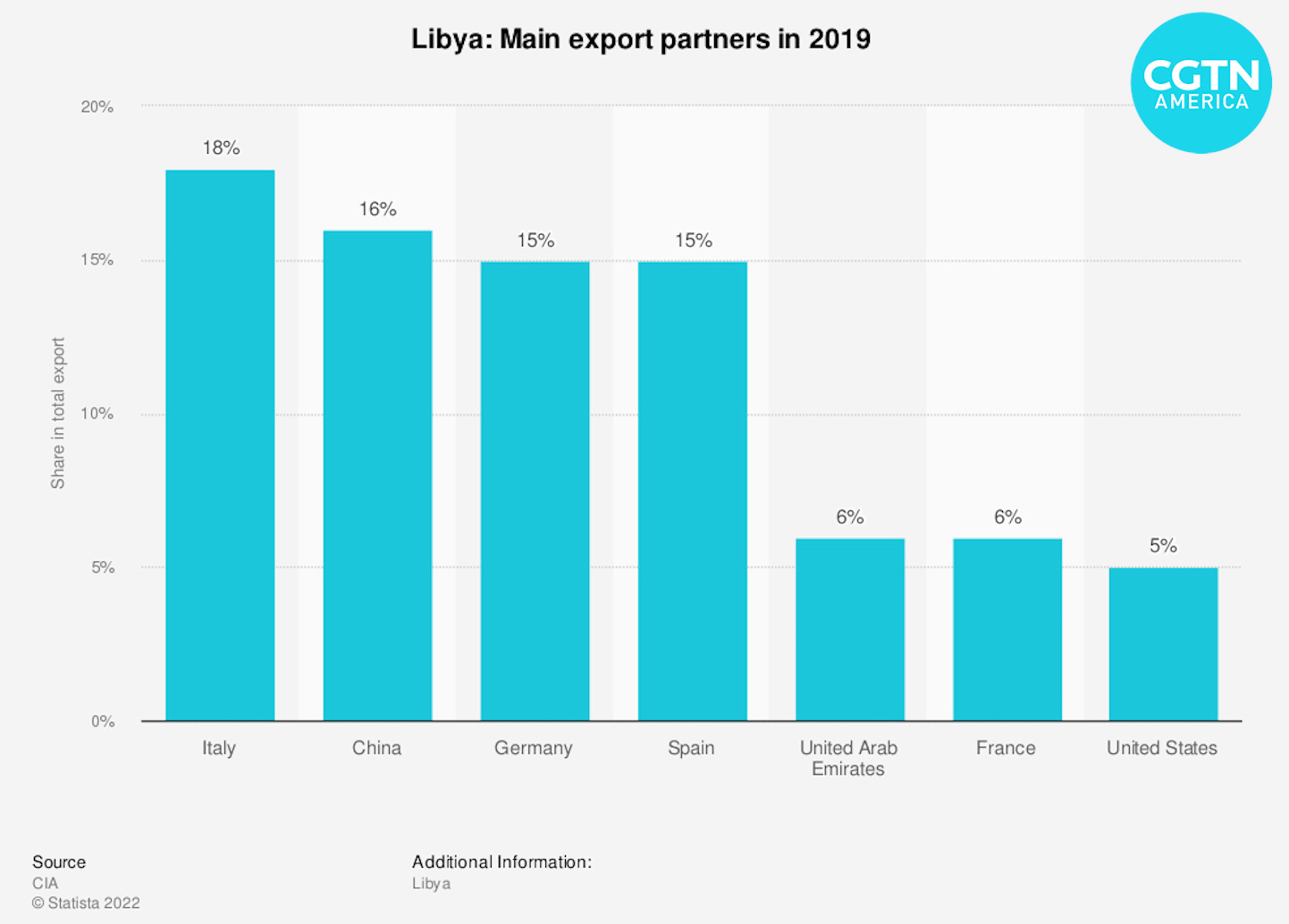

Control over revenues from Libya's main export, its oil output of up to 1.3 million barrels per day, has long been the most valuable prize for all of the country's major political and military forces.

Previously, groups shut down output to put pressure on the government in Tripoli, where all foreign oil sales revenue is channeled into the central bank through international accords.

Forces linked with Haftar, whose control spans across much of the territory, including major oil fields and export terminals, have been responsible for the most significant shutdowns in recent years.

The previous stoppage, which cut exports by almost half, ended when Prime Minister Dbeibah replaced the president of the National Oil Corporation with a Haftar friend, a move some interpreted as an attempt to court the eastern commander and make him more open to a political compromise.